Breaking ground seventy-years ago on this day, we bring you all you need to know (and a few things that you didn’t) about the Palace of Culture & Science…

Breaking ground seventy-years ago on this day, we bring you all you need to know (and a few things that you didn’t) about the Palace of Culture & Science…

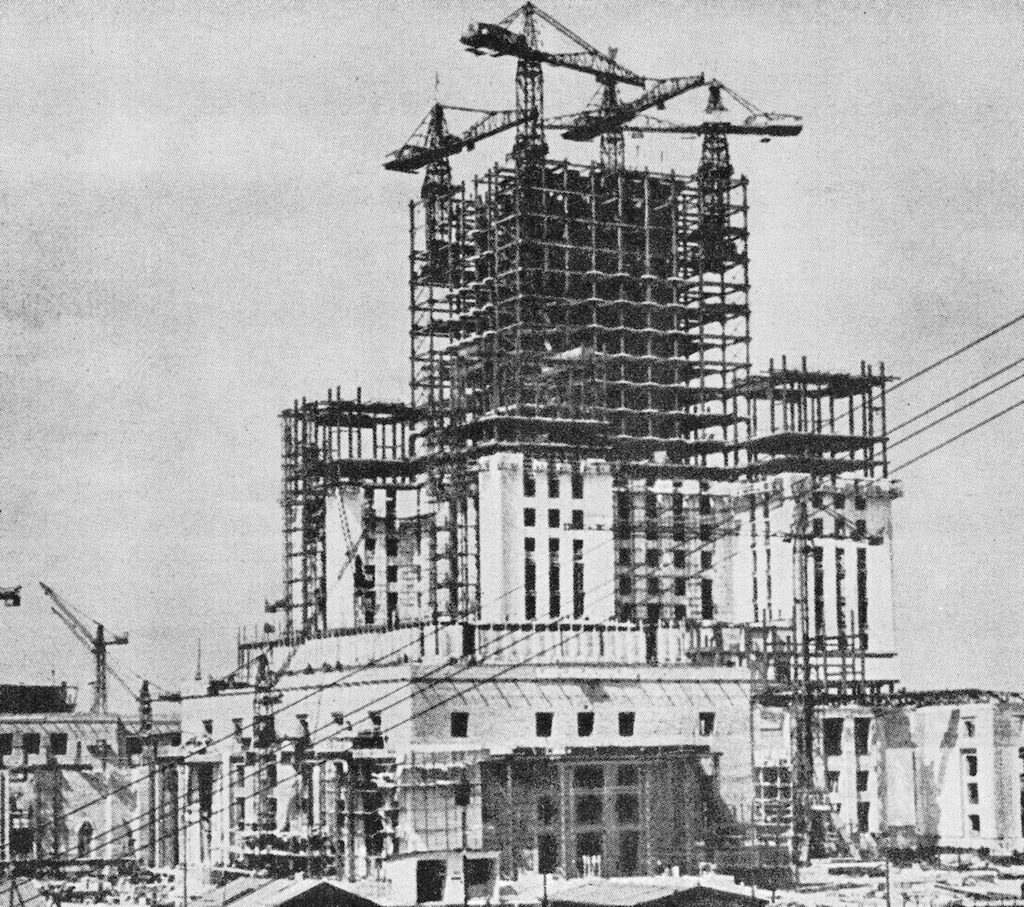

May 2nd, 1952: ground is broken on what, to this day, remains Warsaw’s most recognizable building. Taking three-years to construct, the idea for the Palace of Culture & Science was first touted in 1949 by Stalin, but it wasn’t until two-years later that a six-hour meeting hosted in the capital’s Belweder Palace saw the Soviet leader’s offer formally accepted.

Leading the architectural side was Lev Rudnyev, an architect whose previous form included Moscow’s Lomonosov University, one of ‘seven sisters’ that looked eerily similar. Heavily modeled on these, the Palace of Culture’s conceptual study was ready within six weeks with Rudnyev’s team drawing inspiration from a tour that took them to Zamość, Kraków, Sandomierz and Kazimerz Dolny.

Not only would PKiN reference the Renaissance architecture of these towns, but its shape was also impacted by what the architects had seen. “They found that pointy, slender structures were a feature of Polish architecture,” writes historian Jerzy Majewski, “hence they gave the building a thinner form than Moscow’s palaces.”

Up Top…

Composed of 46-floors in all, the building originally stood at 230 meters and 68 centimeters in height, a size that grew to 237 meters in 1994 after an antenna base was added. At the time of its completion it was Europe’s second tallest building, and for decades it reigned as Poland’s tallest – a crown lost only last year to the Varso Tower.

As a regular visitor, the highest you’ll be able to go is to the 30th floor where a viewing platform can be reached by lift in just 19-seconds. Reportedly, the overall height of the building was decided thanks to a hot air balloon flight. Relaying messages to the pilot by radio, Polish architects shouted, “that’s enough,” as the balloon rose up.

… And Down Under

The Palace extends two-floors below ground, and this tangle of subterranean passages are riddled with mysterious pipes and spigots and Bond-like chambers from which the workings of PKiN are actually controlled. Also containing elements such as original doors, bits of masonry, Soviet banners, buttons from the first elevator and workers’ tools, a tour of its underground is an eye-opening must.

In Facts & Figures

The numbers are mind-boggling. Home to 3,288 rooms, the Palace was built using 40 million bricks that were first produced in the Soviet Union before being ferried over. Featuring a total volume of 815,000 cubic meters, it was built by 4,000 Poles and an estimated 3,500 workers that came in from the East. Sixteen of these died, and today their remains rest in the city’s Orthodox Cemetery.

Formally opened on July 21st, 1955, on December 17th of the same year it’s half-a-millionth visitor filed through the door. By 1958, it was reported that the palace had received 20 million guests, including 1,258,000 to the top floor. The first suicide, meanwhile, was recorded on October 14th, 1958.

An Animal Kingdom

Originally 60 cats were ‘employed’ to keep the building free of rodents, a number now reduced to eleven. Years ago, one managed to cut the building’s energy supply after chewing through a cable. Elsewhere, a 6th floor apiary exists, whilst the 15th floor is home to kestrels. The highest permanent resident, though, are the peregrine falcons that nest just under the building’s spire.

They Were Here!

Even before PKiN was completed, it was a popular attraction for high-profile guests. Indira Gandhi and Kruschev both visited in 1955. Later, in 1971, Leonid Brezhnev spoke here to wild applause. Outside of politics, 1961 saw the Palace visited by the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, whilst iconic performers included Ella Fitzgerald in 1965 and Marlene Dietrich the year before – her performance was disrupted when a cat strayed on stage.

Sparking riots, it was the 1967 visit of the Rolling Stones that is most remembered, with the band allegedly paid in vats of vodka. Unable to take these back to England, it’s said that for years the Palace’s workers flooded the black market with supplies stored in the basement.

The Cultural Side

This flourishes to the present. Home to two museums (including the recently reopened Museum of Technology), the Palace’s offer includes four theaters, one cinema as well as numerous bars. Most socially engaged of the lot are Bar Studio and Café Kulturalna, both of which have assumed a mythical status among their artsy regulars. Lesser-known, the palace also has a swimming pool complete with diving boards and a dramatic skylight all of which were fully renovated in 2016.

The Future

Seen by many as “a tyrannical phallus” that acted as a reminder of Moscow’s influence over Poland, the fall of communism – and its subsequent aftermath – sparked intense debate as to the structure’s future. While it survived these initial calls for its destruction, the discussion has refused to subside: even five-years ago, the Deputy Minister of Defense called for its demolition by the army’s sappers, whilst Radek Sikorski, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, jokingly suggested selling the rights to flatten it to the producers of Bond. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has again seen such solutions openly vaunted.