Sezam

Marszałkowska 126/134

Marketed as the country’s most modern department store when it first opened in 1969, Sezam enjoyed its golden years in the 70s before Poland’s economic collapse rendered its shelves all but completely bare. Later known for an extension that contained Poland’s first ever McDonald’s, its eventual demolition in 2015 saw its signature neon saved and carted off to the Neon Museum. In a sensitive nod to the past, a sign mimicking the old was installed in 2018 when Centrum Marszałkowska was opened on Sezam’s old address.

Wielka Warszawa

Marszałkowska 77/79

One of the city’s newer signs was conceived by artist Arek Vaz, and was implemented as part of the city’s public ‘participatory budget’. Shown is the ‘General Plan for Great Warsaw’, an urban spatial plan that was developed in 1928 by a team of architects and engineers under the direction of Stanisław Różański. With Warsaw’s population projected to triple to up to three million residents by 1958, Różański’s team sought to counter the chaos of such a population explosion by establishing new districts and infrastructure that would readily absorb the rising numbers of people.

IZIS

Marszałkowska 55

Hailing from the 70s, and with an older (uglier) brother on Pl. Bankowy, this neon flags the presence of a health and cosmetic clinic present on Warsaw’s map for over eighty-years. With its rich, red colors and enormous size, few neons in town make such a visual impact.

Coca Cola

Zgoda 13

A candidate for Warsaw’s highest neon, the Coca Cola sign crowning the residential tower at Zgoda 13 has become an established fixture on the city’s skyline. Part of the so-called ‘Eastern Wall’ – a brutal architectural development built to give a counter-balance to the hulking Palace of Culture – it offers the perfect clash between Western consumerism and dour PRL era aesthetics.

Jaś & Małgosia

Al. Jana Pawła II 57

It’s this sign that kick-started Warsaw’s modern love of neon. Returned to its spiritual home in 2014 (above an old commie bar that itself had relaunched in a more modern guise), courtesy of a crowdfunding campaign organized by David Hill and Ilona Karwinska, the pair were so taken aback by the response that it galvanized them to create the city’s Neon Museum. “We saw how attached people were to neon,” says Hill, “and how desperate they were for it to return. If nothing else, it was a magnificent public outpouring of affection.”

Miło Cię Widzieć

Most Gdański

Meaning “Nice To See You”, the neon decorating Most Gdański is actually hanging there by default. Part of a 2014 competition to find “a new neon for Warsaw”, the winning entry was disqualified after a cash-for-votes scandal was exposed, leaving the field open for Mariusz Lewczyk’s idea instead.

Zodiak

ul. Wiecha 4

The Zodiak pavilion reopened in 2018 as a community-driven center of “architectural dialogue”. Along with a snazzy mosaic titled “Kosmos”, the neon is an evocative reminder of its groovy sixties roots.

Wedel

Szpitalna 8

Revealed in 1926 after being commissioned in 1926 by Jan Wedel – the Willy Wonka-style heir of the Wedel chocolate empire – the neon sign crowning the firm’s flagship store was the work of Italian artist Leonetto Capiello. Often regarded as ‘the father of modern advertising’, Cappiello’s design featured a boy on a zebra carrying chocolate bars on his back. Said to symbolize happiness and joy, and consisting of 61 separate neon tubes, the 1.2 ton neon was finally restored a couple of years back.

Metro Płocka

Płocka

Opened in April with next to no fanfare due to the lockdown, word of what awaits at Warsaw’s newest metro stop is only just seeping through. Notable for it eye-catching neon flourishes, Płocka sets a new aesthetic standard that the city’s other public transport hubs fail to remotely challenge (all that is other than Młynów, the other station to open at the time).

Orbis

Jerozolimskie 11/19

In a city still buried in rubble and grappling with the concept of Stalinist rule, the 1951 illumination of the capital’s first post-war neon – a glorious globe advertising Orbis, the state-run travel agency – could not have been viewed as anything other than a dark joke played at the expense of locals with no chance of ever seeing foreign lands. Regardless, it’s unique form has since made it an iconic and much-loved part of the downtown nightscape – to some, anyway. “It’s like living next to a giant disco light,” complained one neighbor when it was restored to its blinking best in 2011.

CeDeT

Bracka / Jerozolimskie

Designed and produced in East Germany as ‘an expression of gratitude’ after the Germans were given use of the first floor to sell their consumer goods, the original serpentine neon that once adorned the CeDeT building was lost in a suspicious blaze that roared through the building in 1975. Now it’s back, with an identical, 4.5 ton replica built in close cooperation with the city’s Monument Conservation Office. First added in 1951, five years after the building originally opened, the return of the structure’s swirly, blue neon sign has won widespread praise from members of the public.

Hard Rock Café

Złota 59

Purists will shudder, but the juxtaposition of the Hard Rock’s glimmering guitar against Stalin’s Palace of Culture in the background makes it something of a modern day classic. Dating from 2007, perhaps no other public installation does a better job of highlighting the schism between then and now.

Volleyball Player

Pl. Konstytucji

First unveiled in 1961, what is arguably the city’s best-known neon depicts a female volleyball player throwing a ball in the air – over and over and over again. Designed by Jan Mucharski, one of the fathers of Polish neon, the sign was first installed to advertise a sports store down below. After years of neglect, artist Paulina Ołowska funded its initial restoration in 2006 through the sale of her own artwork. “I liked that it features a strong, dynamic woman,” said Ołowska at the time, “and I was keen to show that neons from that era could be seen as equals to contemporary works of art.”

Watering Can

Hoża 13A

Marking the HQ of the city’s “Green Board”, this new-ish eye-catching sign needs little explanation – and that’s not a bad thing given the paucity of information circulating about it. But then and again, do pretty things even need a back story?

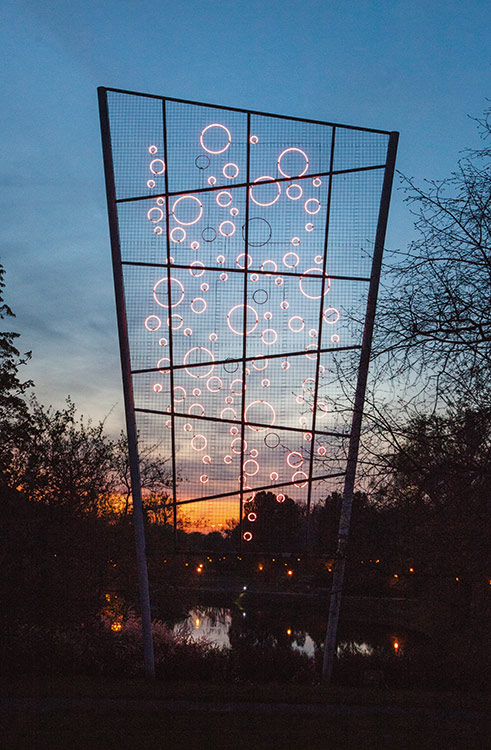

Bubbles

Kępa Potocka

Designed by Maurycy Gomulicki, an eccentric artist with an air of Ziggy Stardust about him, work on this 17-metre installation lasted two years with the results speaking for themselves. Featuring a series of pink bubbles clinging to a sheet of wire mesh, this renegade artwork was devised so as to celebrate “the joy of life and the beauty of the moment.”