Commissioned by the E. Wedel chocolate company, the apartment block at Puławska 28 has long been a source of fascination for Warsaw’s architecture buffs…

Commissioned by the E. Wedel chocolate company, the apartment block at Puławska 28 has long been a source of fascination for Warsaw’s architecture buffs…

Financed by Poland’s chocolate king Jan Wedel, the property was one of many on Puławska belonging to the family. Arguably the most high-profile, the acclaimed architect Juliusz Żórawski was recruited to design it. Following Le Corbusier’s five principles of modern architecture, the building featured horizontal strip windows, a main body raised on columns, a rooftop terrace for recreational purposes, an undeveloped ground floor, and a façade largely free of unnecessary embellishments.

Built between 1935 and 1936, what arose must have seemed truly futuristic. Clinker tiles covered the external walls, and a bas relief was added above the corner entrance. The work of Stanisław Komaszewski, it depicted a tiger prowling through a marsh.

Other artists were also enlisted by Wedel. Rated alongside Tamara de Lempicka and Olga Boznańska as among Poland’s top female creatives of the inter-war period, Zofia Stryjeńska was contracted to paint the entrance hall where a Wedel chocolate store stood. After collecting her fee, the artist then put the commission to the back of her mind. Uninspired by it, she continued to procrastinate. Fearing Wedel’s wrath, she even paid her porter to make excuses on her behalf and claim she was away. At one stage, she considered fleeing abroad to avoid Wedel, but eventually finished the painting after negotiating an extension to her deadline.

Taking eight-months in all, the final result was a work titled ‘The Highlander’s Dance’. Covered up in the 1960s, it was only rediscovered decades later. Today, it sits safely behind a protective plexiglass cover. Other works were not so lucky. Komaszewski had also contributed a sculpture of a goat that stood in a decorative courtyard pond. During the 60s this was considered surplus to requirements and removed. With the sculptor dying in German captivity in 1945, and so much of his output lost during the Warsaw Uprising, his tiger at the entrance is a rare surviving example of his work.

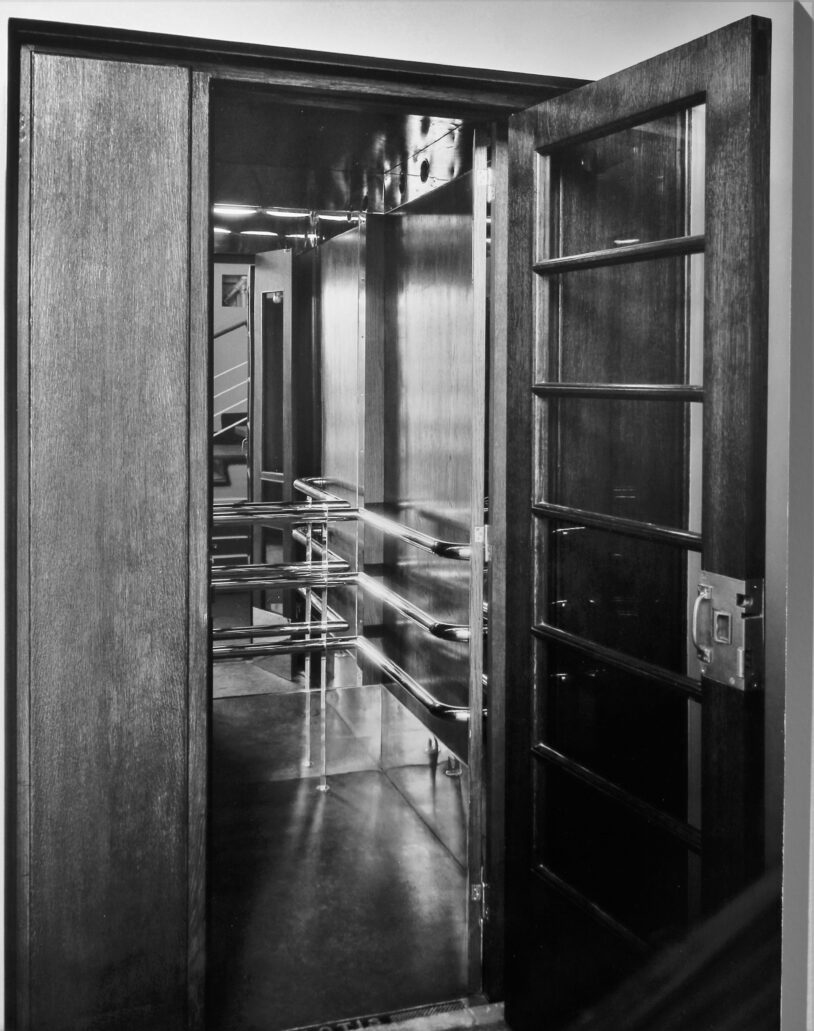

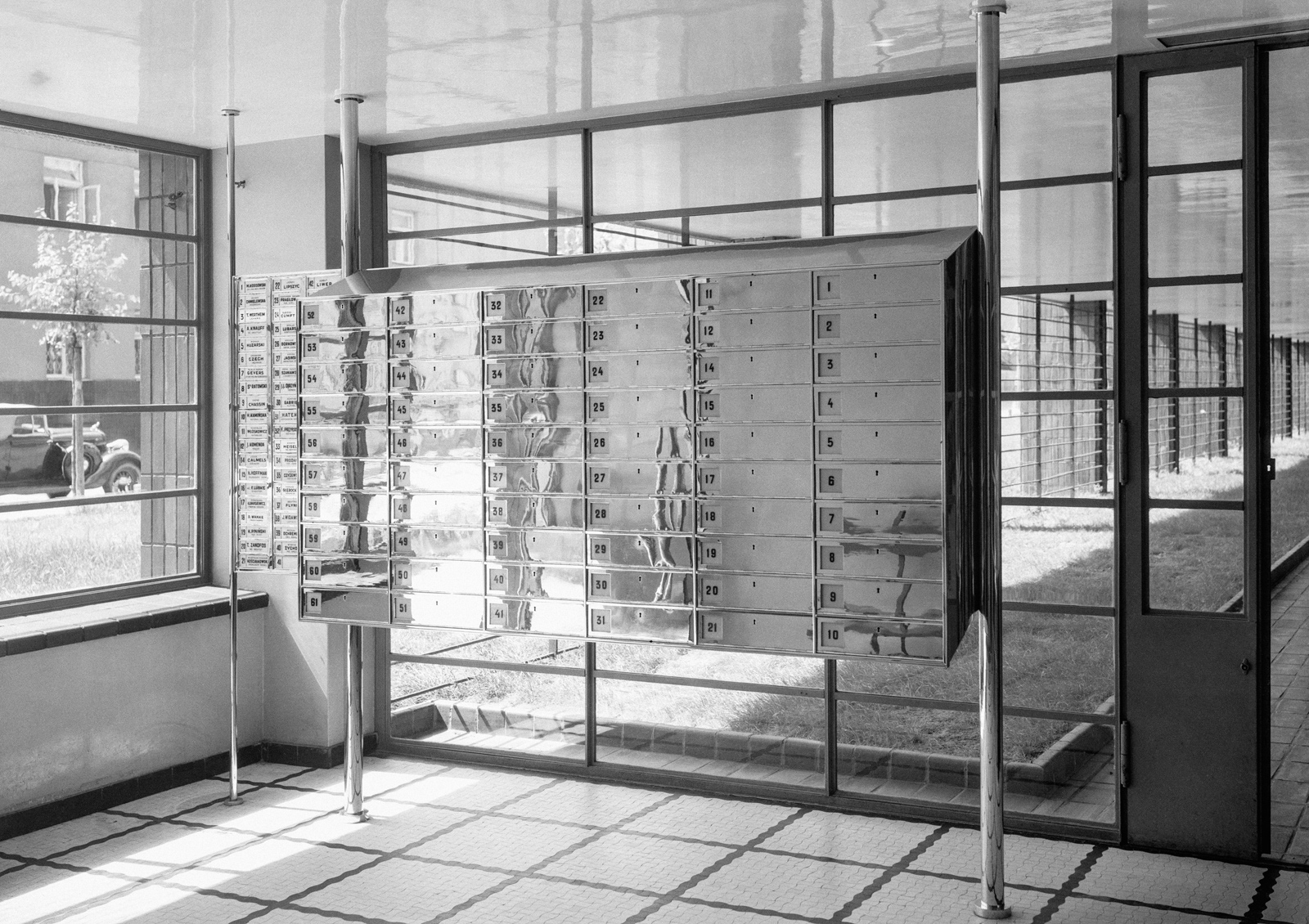

Luxurious for the time, the apartment block was equipped with swanky elevators, chrome-plated mailboxes, waste incinerators, terracotta-lined stairwells and a radio antenna. This was not the only adornment crowning the top. In 1938, a neon was added proclaiming E. Wedel on the Madalińskiego side and Czekolada on the Puławska side.

To all intents and purposes, the apartment block was a vision of pure, modernist aesthetics. Naturally, this was appreciated by the Nazis and during the occupation it housed officers and Gestapo officials. This made it an insurgent target, and during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising it came under heavy attack by the Baszta regiment of the Home Army. Despite their best efforts, they were unable to dislodge the Germans.

In later years changes extended beyond just the removal of art. The ground floor was filled with stores and the pre-war neon sign removed after the nationalisation of the Wedel chocolate factory – only in 2019 was a replica erected. Once pockmarked with bullet wounds, these were covered during a controversial renovation in 2008. Even so, other details have remained true. To this day, for instance, the block’s numbering system does not have a No. 13. Relevant even in contemporary culture, it played a starring role in Szczepan Twardoch’s 2012 breakout novel Morfina.