More than offering a mere bed for the night, this issue join us for a look at the Warsaw hotels that helped rewrite history…

More than offering a mere bed for the night, this issue join us for a look at the Warsaw hotels that helped rewrite history…

Nowadays, most locals call the building that towers over Pl. Powstańców Warszawy the Warszawa after the hotel that it houses. This, however, was not always the case. Completed in 1933, and put into use the following year, this early skyscraper was originally titled the Prudential in honor of its principal tenant – the globally renowned British insurance firm.

Initially intended measure just 11-storeys, this was increased during the planning stage to 16-floors in all. Heavily influenced by the trans-Atlantic skyscrapers trending in cities like New York and Chicago, Marcin Weinefeld’s project became Poland’s tallest tower. In, in Europe only the 96-meter Boerentoren in Antwerp beat it for size. Visible from 20 kilometers away, its height wasn’t overlooked by Poland’s television firms and in 1936 the roof was handed over to house the nation’s first TV transmitter.

But although Prudential could be considered the flagship tenant, the building’s higher floors had been set aside for several apartments that were, at the time, considered among the most luxurious in Warsaw – the biggest penthouses covered a whopping 240 sq/m.

Constructed using two million bricks, two thousand tons of concrete and one-and-a-half thousand tons of concrete, it was a building whose huge dimensions were matched by the luxuries within: there were frescoes by Wacław Borowski, one of the country’s leading artists of the era, walnut furniture by Nina Jankowska, and a heap of alabaster and marble trimmings.

Its importance did not diminish during the occupation and the Prudential’s height made it a pivotal Home Army target once the 1944 Warsaw Uprising kicked-off; realizing the morale boost it would give citizens were they to see the Polish flag flying from the nation’s tallest building, capturing the building was an early priority – it’s fall sparked scenes of wild jubilation. “When the Polish flag was hoisted from it, people left their homes just to look at it, crying and laughing and spontaneously singing the national anthem,” wrote historian Alexandra Richie.

The German response was ferocious and the building was subsequently battered by 1,000 rounds of artillery. On August 28th, 1944, it was struck by a two-ton shell but still its steel skeleton held firm – captured on Sylwester Braun’s Leica camera, his images of the resulting explosion would become iconic.

Never captured in battle, the Prudential only returned to German hands when the city’s surrender was signed – a symbol of stubborn defiance, it had withstood everything the Nazis had thrown at it. Even so, it made for a sorry sight. Filled with over nine thousand tons of rubble, it would take years for it to be restored. Leading these efforts was the original architect, who himself had survived the war by the skin of his teeth having been imprisoned in Dachau.

Due to the new political reality, Weinfeld’s first design was simplified to fit the concepts of Socialist Realism, and more floors were squashed in thereby giving the building a more cramped feeling. Still, its renewal was welcomed, and when it relaunched in 1954 it was to fulfill the function of a hotel. It was named the Warszawa.

Famous for its social gatherings and black tie balls, for a short while the hotel became the pride of PRL Poland; the glory years did not last. When Communism collapsed, the hotel too found itself falling from grace. Looking increasingly dark and dowdy, it was finally closed in 2003. Fortunately, this was not the end.

Purchased by the Likus family in 2009, there could have been no better buyer for this historic property. Already known for luxuriously recharging a string of heritage addresses in Kraków, Wrocław and Katowice, their patient revival process saw the Warszawa finally reopened in 2018. Spectacular and contemporary yet also tastefully restrained, the rebooted Warszawa now stands out as one of the most exciting stays in Central Eastern Europe. High on natural materials, and looking teasingly minimalistic, the design-forward style is a sensuous joy.

The 2018 launch of the Raffles Europejski Warsaw was the culmination of a meticulous renovation that saw no expense spared. But so much more than just another sumptuous hotel, its inauguration marked the return of an iconic building that has often been at the forefront of the trials and triumphs experienced by Warsaw.

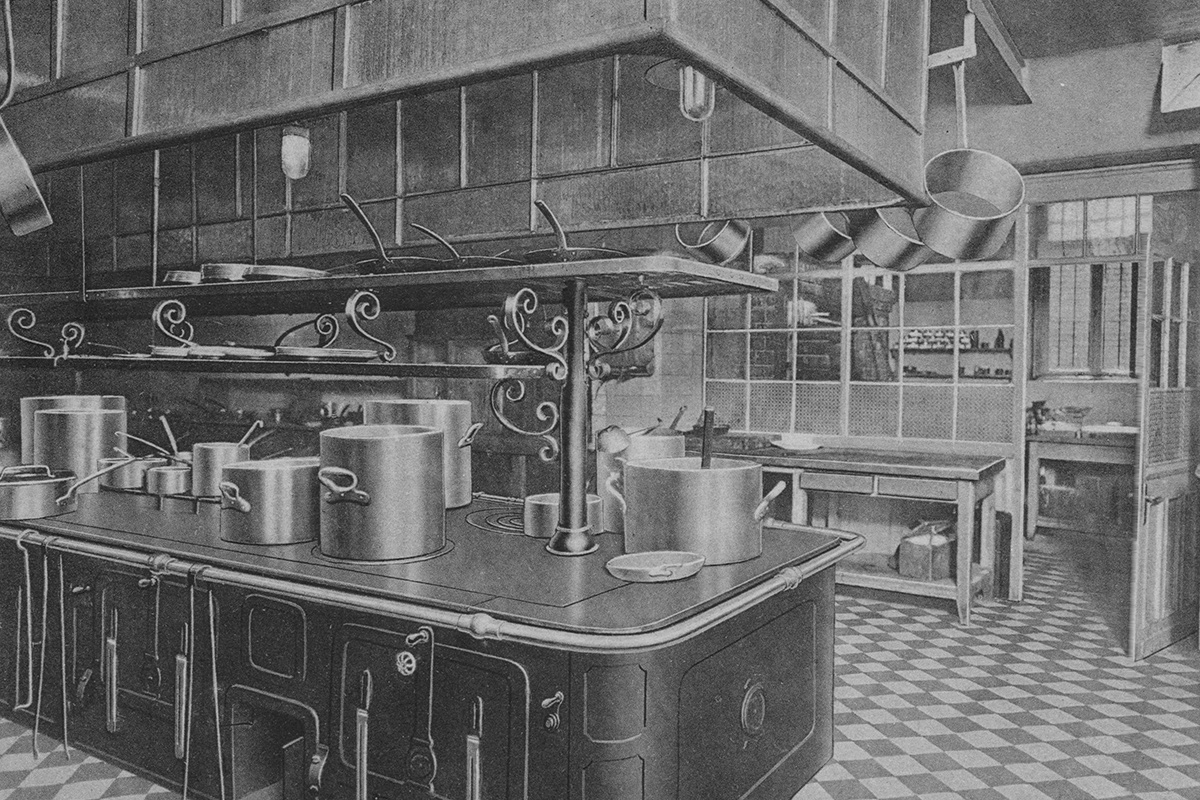

Originally opened in 1857, Henryk’s Marconi’s Neo-Renaissance design for the Europejski was complemented by lavish interior touches by his son, Karol, and his nephew, Ferrante. Impressing from its inception, people traveled from far and wide to enjoy the cooking of Józef Wysakowski, the former chef to Spain’s Queen Isabel – quickly, the hotel earned a reputation as arguably the most elegant in the entire Tsarist Empire. Refusing to stand still, further improvements were made to coincide with its 50th anniversary; partly goaded by the opening of the Bristol across the road, the upgrade included the introduction of sound-proofed doors, electric elevators and telephone booths.

The stars of the day flocked there (among them, the avant garde painter Witkacy and actress Helena Modrzejewska, a.k.a. Poland’s most beautiful woman), and the Europejski’s glittering New Year’s Eve parties found themselves immortalized after being featured in The Doll (Lalka), a 19th century classic that has come to be regarded as the greatest literary work in the history of Poland.

Rechristened the Europäisches in 1939, the Nazi occupation saw it designated as Nur für Deutsche and for the following five years its corridors clicked to the goosestepping jackboots of visiting German officers. Heavily damaged during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, it reopened as a hotel in 1962, albeit a pale shadow of what it once was. Nonetheless, the lack of competition saw it maintain its reputation as the city’s top hotel, and as such the big names continued to check-in.

Of the ‘slebs that lodged at the post-war Europejski, Marlene Dietrich was one of the first with the chanteuse snootily complaining that the lift wasn’t large enough for her four-meter fur (in a huff, she switched to the Bristol opposite). Next came The Rolling Stones, with their two landmark gigs prompting riots around town. According to legend, their press conference at the Europejski only went ahead following a last-minute bribe, while other anecdotes claim they finished their first night in Poland drinking vodka and crawling back to their rooms “on all fours”.

Of course, not all high-profile visits were as chaotic, and one of the hotel’s prouder moments came in 1970 when Willy Brandt signed a declaration officially normalizing relations between Poland and Germany. Soon after, the West German Chancellor would send further shockwaves across the world by dropping to his knees in front of the Jewish Uprising Monument in Muranów.

For the Europejski, however, the years that followed brought only gloom, a decline finally halted when a 2005 court ruling returned it to its rightful pre-war owners. Working in tandem with Raffles, the resulting restoration has seen the hotel become a benchmark in luxury and a showcase of the finest Polish art and craftsmanship. Fittingly, among the first VIPs to stay were the Rolling Stones. Visiting Poland as part of their No Filter tour, it was a clear affirmation that this stunning hotel had returned to its rightful perch. Truly extraordinary in every respect, the Raffles Europejski Warsaw has bridged the past with the present in peerless fashion – that it also doubles as home to outposts of Hermes, Aston Martin and Brunello Cucinelli only serves to underline its blue ribbon reputation.

Celebrating her 120th birthday last year, few hotels can match the story of the Bristol. Named so after the Earl of Bristol, a famously extravagant and worldly 18th century traveler, this Warsaw legend welcomed its first guest on November 19th, 1901. Reportedly arriving from Paris, Emilia Finot crossed the threshold to be greeted by the hotel’s GM, a man history remembers only by the surname of Helbling.

Setting a groundbreaking standard, she was whisked on a tour of a hotel that contained thrills such as central heating, double ventilation and a staggering six telephone lines. The star attraction though was a crystal lift, a contraption deemed so exotic that the hotel hired an attendant to make sure that users didn’t faint with excitement. The press corps, who had queued rowdily on the stairwell for their preview, wrote of little else than this “fairy tale carriage”.

Mirroring Poland’s own inter-bellum golden age, the Bristol too enjoyed the 20s and 30s to the max. It was then that Prime Minister Ignacy Jan Paderewski chaired his first government meeting inside the hotel, thereby giving birth to modern Polish democracy in the process. In fact, such was his liking of the property, he took a suite here that today has been preserved as a nationally protected monument. More than just an object of historic curiosity, today it doubles as the hotel’s most prestigious suite.

Famed for its lavish social events, the Bristol also saw its fair share of drama – when Józef Piłsudski announced his retirement from politics, it was in the Bristol’s hallowed halls. Though never destroyed during the war, a fact owing to the favor it found with German high command (one section became the HQ of the Chief of the Warsaw District), peacetime found the Bristol looking apologetic.

Still, the first couple of decades saw no shortage of VIP custom, and of those to traipse through the entrance were Marlene Dietrich, Pablo Picasso and JFK. But with investment lacking, the hotel was closed in 1981 and only revived once Communism fell. Purchased by the Forte Group, an extensive renovation was undertaken and the hotel was reopened by Margaret Thatcher in 1993. Signaling a return to the good times, the hotel became a bi-word for quality, a fact highlighted by the visitors it would attract in the ensuing years: Bill Gates, Paul McCartney, Tina Turner, Sophia Loren and Woody Allen to name but a few.

Famously, when George Bush arrived at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to give a speech, it was one of the hotel’s concierge staff that came to the rescue when it was realized that the President had left his coat in Berlin. Rushing to his aid, an overcoat belonging to a concierge was delivered just in the nick of time by the Bristol’s head of operations.

Rated as one of the most famous hotels in Central Eastern Europe, today the Bristol continues to evolve mixing its powerful sense of history with the modern day demands of the five star traveler.

Hints as to how majestic Warsaw once looked can be found on that stretch of Jerzolimskie that runs from Rondo Dmowskiego to Emili Plater street – scanning the buildings that line this route, its easy to understand why Warsaw was once known as the ‘Paris of the East’. But imperious as these structures are, none look as grand as the Polonia Palace Hotel.

Opened on the 14th of July, 1913, its name was no accident. Founded at a time when Poland still fell under Tsarist rule, its title was picked by the hotel’s founder, Konstanty G. Przeździecki, to remind the citizens of Warsaw that Poland “should always exist in the heart and mind”.

From the outset, it was quite a hotel. Though competing against heavyweights such as the Bristol and Europejski, it offered modern conveniences the likes of which were unavailable in rival hotels: among these trimmings, guests had access to typewriters and fireproof deposit boxes. Also offering “transport solutions” to the city’s train stations, its location was another big boon.

Located just strides away from the Warsaw-Vienna station, its coordinates ensured a constant footfall of visiting dignitaries, including the King of Afghanistan in 1929. By this time, the hotel was already synonymous with the high life, and 1924 saw the garage converted into a dance hall and ballroom whose artistic director was Ralph Roy, an award-winning dancer from Vienna. Attracting a string of VIPs, those that gathered for the Polonia’s banquets and balls included Stefan Żeromski, Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński and the legendary tenor and actor Jan Kiepura. In 1929, the hotel hosted the first ever Miss Polonia competition, a pageant won by Władysława Kostakówna – passing away in 2001, Kostakówna would later finish runner-up in the Miss Europe contest, before going on to be awarded for courage for her work as an agent during WWII.

Undoubtedly, it was this era that was to prove the most challenging for the hotel. Already hailed for its extensive wine cellar, trendy perfumery, hair salon and chlorine-free laundry service, it was little wonder that it was seconded by the occupying Germans and it became a favorite haunt of visiting officers. Captured during the Warsaw Uprising, it served as a field hospital and supply center and only survived destruction after loyal staff risked all by returning after the capitulation to lock the hotel down.

It was because of their courage that the Polonia became the only hotel in the city to withstand heavy destruction, and this made it a natural choice for embassies seeking a post-war address in the ruined city center. Most famously of all, it was here where General Eisenhower stayed in 1945 whilst touring the devastated city.

The PRL era saw the Polonia treated well, and in 1953 it hosted a famous diplomatic banquet – attended by Zhou Enlai, the first leader of the People’s Republic of China – during which chefs created dishes such as a horse-drawn carriage made from cold cuts and ‘burning ice cream boats’ that featured batteries and lights inside. Never short of celebrity custom, the following decades drew visits from legendary footballers such as Zbigniew Boniek, Grzegorz Lato and Jan Tomaszewski (the goalkeeper that thwarted England at Wembley in 1973) not to mention performances by the biggest domestic bands of the time: Czerwone Gitary, Skaldowie and Słowiki.

Temporarily closed at the beginning of the millennium, major restorations occurred in 2004 and 2010, and these have returned the hotel to its standing of yore. Beautiful to explore, it’s a hotel whose history and tradition ring loud and proud.

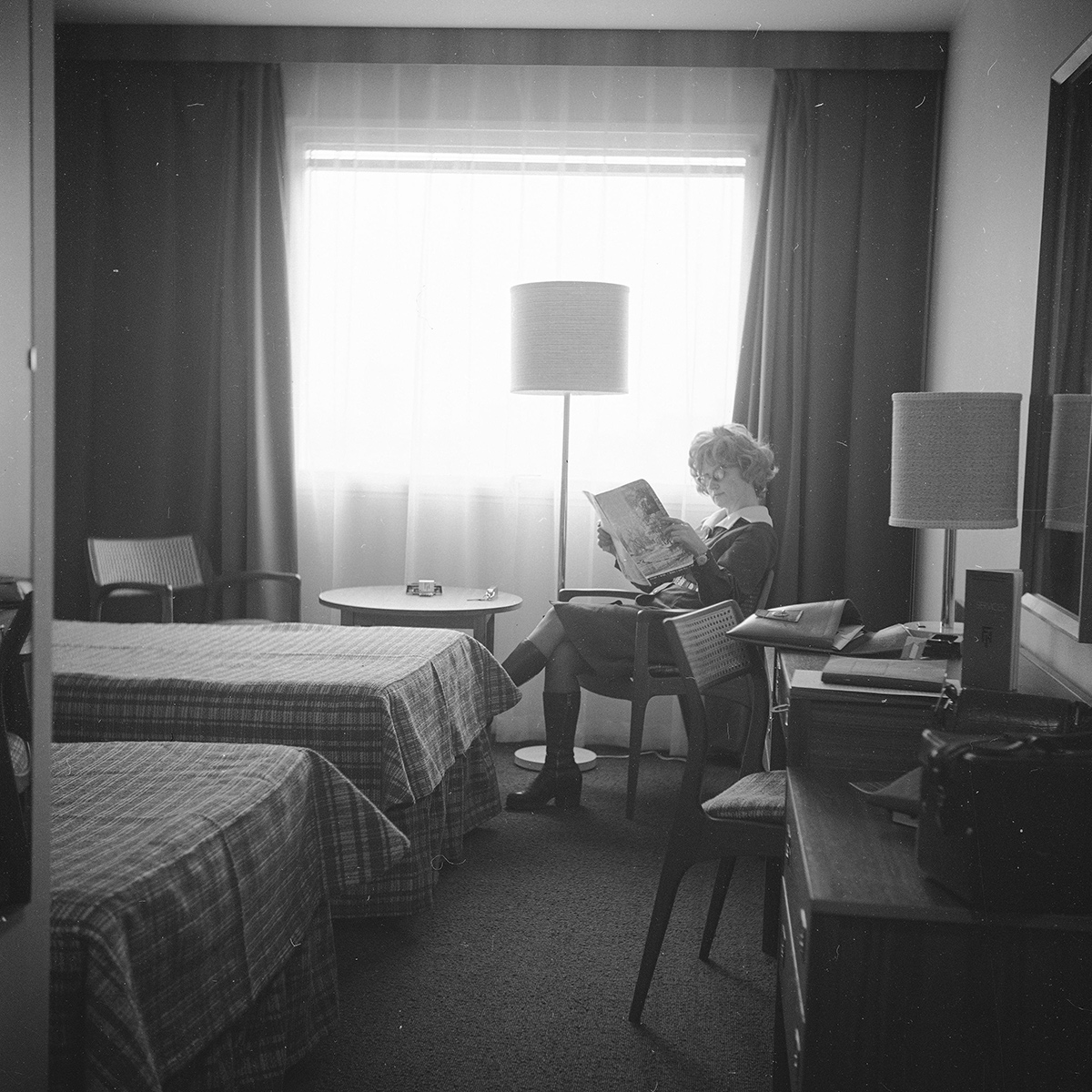

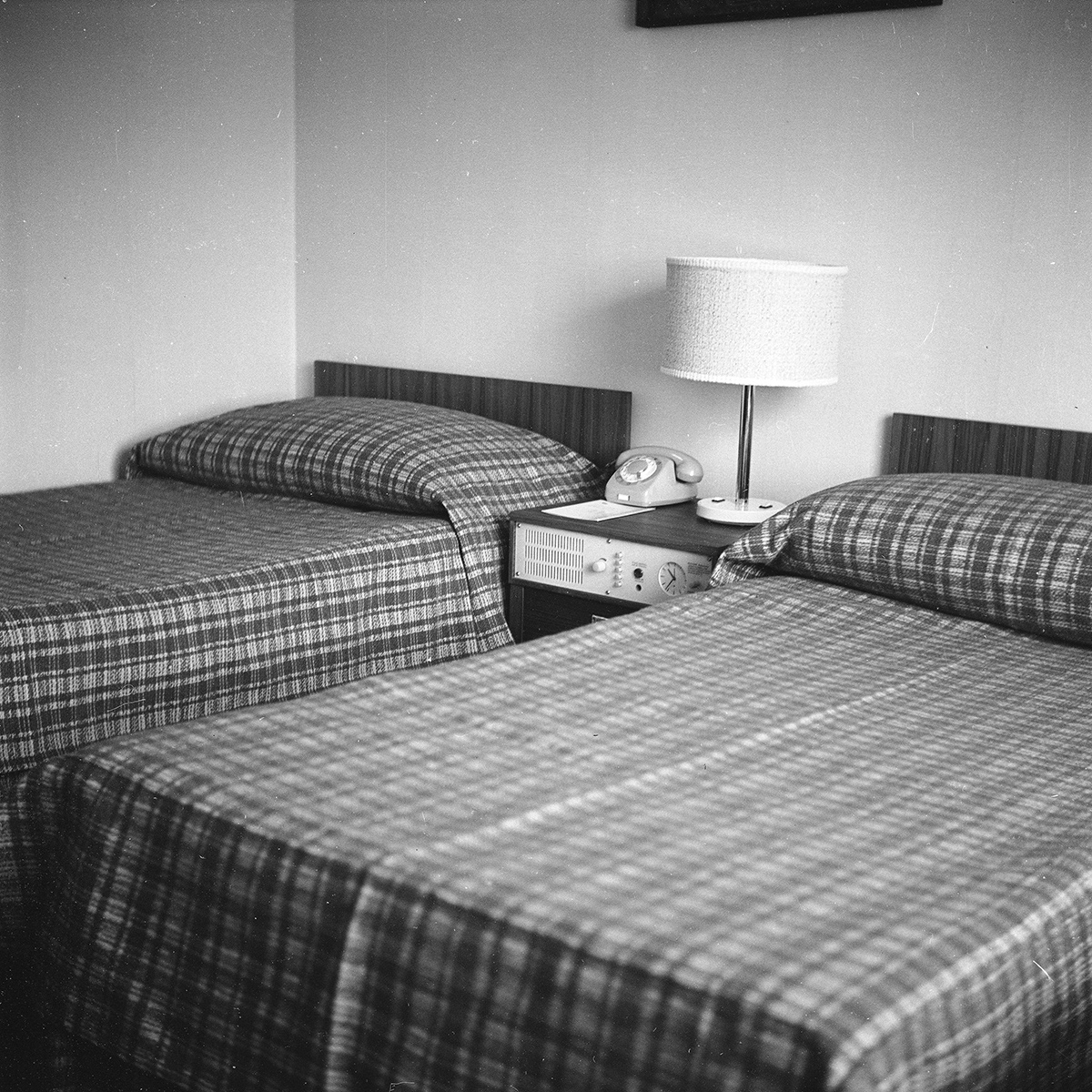

Today, you’ll likely know it as the Novotel, but back in the 1970s the tower that loomed over Rondo Dmowskiego identified itself as the Forum Hotel. Opened on January 24th, 1974, it was touted as being “the first Western style tower in the city”. Designed by Sten Samuelson, not everyone liked it, and its sandy-brown façade saw it quickly dubbed ‘the chocolate bar’ by unimpressed locals. Standing 96-meters high, what was then Poland’s second tallest building had several detractors with one critic, Jerzy Waldorff, going so far as to claim the architect had avenged Sweden’s 1656 defeat at The Battle of Częstochowa with his design.

But the Swedish connection did not end here. Most famously, ABBA used the Forum as their base when they visited Poland in 1976. Reputedly booked after the Polish authorities promised to export tons of canned peas to Sweden, the pop megastars were besieged by fans at the Forum, though did manage to squeeze out through the delirious mob record a TV program, tour the Palace of Culture and neck some vodka in the Old Town. Formerly also used as the seat of embassies representing Libya, Gabon, Costa Rica and Portugal, the hotel was rechristened the Novotel in 2002. Modernized a couple of years later, its jaundiced skin was replaced by the sleek, silvery façade we see today.

When the Marriott opened in 1989 it marked the end of a stop-start construction process that had lasted twelve years in all. Taking root on a plot that had been empty since the war, the original plans – drawn-up in the 1960s – were almost sci-fi in their style and imagined a futuristic complex consisting of ice rinks, pools and skyscrapers linked together by footbridges and cable cars.

By the 70s, the blueprints had been amended and simplified but even so the project found itself halted for several years after the implosion of the domestic economy. Resumed in 1987, work finished two-years later thanks, in part, to the efforts of Thai construction workers flown in for the job. An oasis of prosperity and American-style largesse, expats and monied locals thronged the hotel’s bars and restaurants, while visiting VIPs made full use of the split-level Presidential Suite on the 40th floor: Joan Collins, Luciano Pavarotti, Chris de Burgh and Michael Jackson to name just a few. Helmut Kohl, too, was here when news filtered through that the Berlin Wall was being swarmed and dismantled.